J.S. Bach: Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat major, BWV 1010 – arranged for piano by Eleonor Bindman (GPC078)

This is the sheet music edition of a new piano arrangement of the Bach Cello Suite No. 4 in E-flat major by Eleonor Bindman.

Solo piano

17 pages

Duration: 21:27

Audio samples

Buy, stream and download the CD here.

Cello Suite No. 4 marks the beginning of the second half of this cycle, the last three Suites being longer, more complex and more difficult to perform. While somewhat awkward for a string player, the key of E-flat major gains idiomatic and expressive facility on a keyboard.

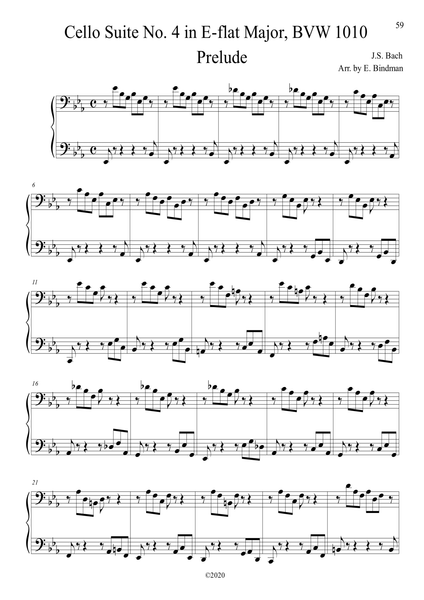

The Prelude sounds almost “Romantic” on the piano and is best described by the overused adjective “beautiful.” What exactly makes it so? Hard to explain, but these arpeggios descending from far above, often traversing two octaves, feel like a gentle stream of kindness, of heavenly grace enveloping us all. The 16-note episodes are clouds passing through, only to return us back to equilibrium. This Prelude perfectly illustrates an important “trade secret” of J. S. Bach: starting a pattern on the second note of a measure, instead of on the first. This compositional device, whether used intentionally or not, is the key to that singular “endless” quality of his music. The rift between the downbeat and the beginning of the arpeggio creates an ambiguity of emphasis and effectively cancels our auditory awareness of the bar lines.

The inner patterns of the arpeggios contain rich layers of implied polyphony and this Prelude works in a wide range of tempi (I currently prefer mm. 52-54 per half note). Starting at m. 49 and through the end, I would suggest following the directional and harmonic implications of the 16th-note fragments without feeling constrained by diligent counting. And by all means, use that damper pedal for the arpeggios, your foot will probably land there before you even know it.

The Allemande brings us back to earth with a distinct accent on the first beat and a general feeling of rhythmic and melodic stability, providing a strong and mutually beneficial contrast to the Prelude. It can be a great warm-up at a slow tempo or a fun romp at a very fast one. I would keep the target tempo at about 80-92 beats per quarter note, since the next movement is traditionally speedier and lighter.

This Courante is true to its name, florid and dance-like. Like the Prelude, it starts with a descending arpeggio, but this is no longer a unifying element of several movements, as seen in Suites 1, 2 and 3. Downward 8th notes switch to upward 16ths, followed by more downward 8ths and then a long string of upward triplets. This variety and balance of rhythmic subdivision is quite remarkable and the unexpected changes, especially when the triplets appear, create a visceral effect, as a new dance step would. I play it at around 120 per quarter note.

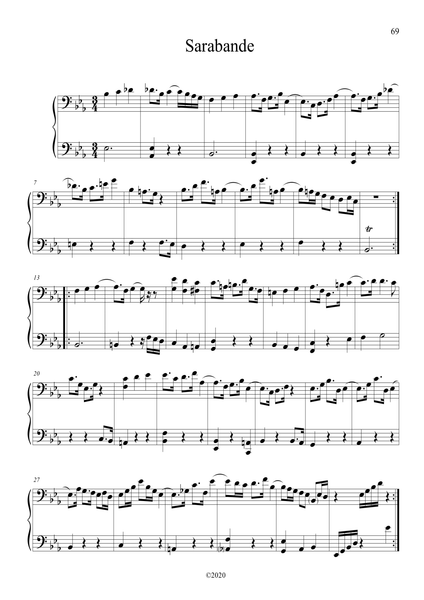

An understated emotional attitude may benefit this particular Sarabande as the rhythmic structure here is sparse, mostly quarter notes and dotted rhythms, and less appropriate for declamatory deviations. To me it’s the most dance-like of the predominantly “philosophical” Sarabandes and the fastest one, around 52 for each quarter beat.

Bourrées I and II mark an interesting transition from the first half of the cycle: they are both in the main key, whereas the Minuets and Bourrées of Suites 1, 2 and 3 alternated parallel major and minor. Bourrée I contentedly toys with a five-note pattern, tossing it around various scale degrees, pairing it up, doubling up the pairs and then inverting it in the second half. The playful style of Bach’s own manipulations seems conducive to fun register changes upon repeats. Bourrée 2 is the shortest unit of the entire cycle, 12 measures of mostly quarter notes, with distinctly syncopated upper part against a steady bottom, as if bouncing the accent around, still in somewhat comical mode. The suggested speed might be 68 per quarter note, with both dances exactly in the same tempo.

The French term “Gigue” derives from the English “jig” and this movement could indeed pass for an Irish jig or an old American fiddle tune, were it written an octave higher and a semitone lower, in D major. The repetitive three-note “lower mordent” pattern winds up the energy and makes us want to stomp our feet, grab a partner and do-si-do. Incidentally, Do-Ti-Do, is the major recurring unit in this great finale to Suite No. 4. Play it as fast as you can.

– Eleonor Bindman